Chapter 9 – Thomas Modyford

|

|

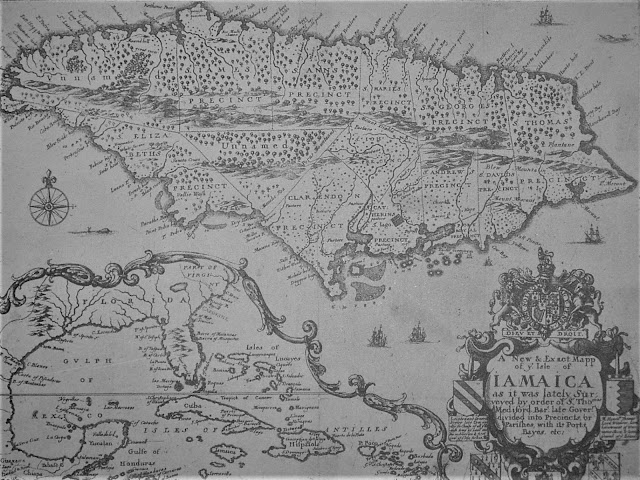

Map of Jamaica Ordered by Sir Thomas Modyford |

The most notable of the recent immigrants was Colonel Sir Thomas Modyford, 1st Baronet (1620–1679). He was the son of a mayor of Exeter who became a barrister of Lincoln’s Inn and had served in the king’s army during the civil war. In June 1647, he sailed with his family to Barbados. There he invested in property and quickly became a wealthy planter. Later, he held the offices of governor and speaker of the assembly.

Readers may remember Sir Thomas as one of Oliver Cromwell’s advisors who favoured a strike by England against Spanish America in 1655 (the Western Design). And it was he who had been so helpful in securing Barbadian recruits for the army commanded by Venables.

|

| George Monck, 1st Duke of Abermarle | Peter Lely |

On 15 Feb 1664, Colonel Sir Thomas Modyford was appointed governor of Jamaica with very full powers and instructions to take any settlers from Barbados willing to accompany him. On 18 February, he was created a baronet to increase his authority.

Sir Thomas arrived in Jamaica on 4 Jun 1664 aboard HMS Marmaduke. He was destined to play a significant role in public affairs and the development of agriculture in Jamaica. Modyford is generally credited with establishing Jamaica’s sugar industry, which became the island’s principal crop. The arrival of sugar cane also created the foundation for Jamaica’s slavery-based plantation society—what some would call its plantocracy—for it was the labour-intensive cultivation of sugar cane and its processing into sugar, molasses and rum that primarily created the need and the justification for a large captive labour force.

Modyford would also form an entente cordiale with Henry Morgan that would secure their places in Jamaica’s history and that of the British Empire. His appointment as governor ushered in the golden era of the buccaneers and the emergence of England as Spain’s chief rival in the New World. No longer could the Caribbean be described as a Spanish lake. With its world-class harbour and its position at the geographic centre of the Caribbean, Port Royal was an English bayonet poised at the very heart of Spanish America.

On his way out from England, Modyford had stopped for some weeks on Barbados. He believed the island was overpopulated and offered free passage and liberal grants of land to several local planters on condition they emigrate to Jamaica, a much larger island. Through these efforts, he attracted several hundred planters who he brought with him to Jamaica.

While at sea, Sir Thomas wrote a polite letter to the governor of San Domingo. He announced his appointment as governor of Jamaica and stated that the King had instructed him to enforce a ban on attacks on ships or territories of Spain. Modyford offered peace with his Spanish neighbours in exchange for a cessation of hostilities on their part and freedom of the English colonists to trade with them. To this, the Spanish governor returned a courteous though evasive reply, which arrived in Jamaica ahead of Modyford.

When the Spanish governor’s response was shown to Colonel Lynch in Jamaica, he reacted with cynicism, stating officially that there was already far too much bad blood between his colonists and their Spanish neighbours for any mutual trade agreement to be useful to Jamaica.

❦❦❦

Modyford chose Colonel Sir Edward Morgan as his deputy-governor and military commander. Sir Edward was one of Harry Morgan’s paternal uncles who we met in an earlier chapter. Sir Edward almost certainly received the post on advice from George Monck, who was then the chairman of the Committee of the Privy Council on the Affairs of Jamaica. Monk, as we have also seen, was closely associated with Sir Edward’s brother, Thomas.

Sir Edward had spent many years in the Low Countries and learned the Dutch language and their military systems. In case of war with Holland—something already being contemplated in London—there would surely be an attempt to capture the Dutch colonies in the West Indies. In which case, Sir Edward’s knowledge would be valuable. When appointed, Sir Edward was given wide scope to carry out his duties. He was also supplied with arms and munitions, but he was instructed to enlist soldiers in Jamaica, for none could be sent out from England.

Sir Edwards’s wife Anna had died in 1662, so it was with his children only that he set sail for Jamaica aboard HMS Watergate and the ketch Swallow. Sadly, his eldest daughter died before he arrived at Port Royal, two-and-a-half weeks ahead of Modyford. He came ashore at the Point in mid-May 1664, took control immediately of the government, and dissolved the Council. Later, Governor Modyford approved wholeheartedly of his actions. Along with his son Charles, Sir Edward also began clearing the land he had received as a grant to go with his new appointment. In time, Charles Morgan would himself become a prominent planter and member of the assembly.

It seems that the king was serious about curtailing hostilities between his West Indian subjects and those of Spain, for he was anxious to engage in peaceful trade with England’s traditional enemy. His instructions to Modyford certainly reflect this.

Accordingly, on 12 Jun 1664, Sir Thomas Modyford published a proclamation declaring all hostilities against the Spaniards must cease. Following this, a special messenger was dispatched to inform the governor of Cartagena, even though Modyford seemed to doubt prospects for the success of the king’s policy. In a letter to his brother in England written about this time, Sir Thomas revealed he had other concerns: with “no less than 1,500 lusty fellows abroad, who, if made desperate by any act of injustice or oppression, may miserably infest this place and much reflect on me.” [Calendar of State Papers, America and West Indies, No. 786, Sir Thomas Modyford to Sir James Modyford.]

Not many weeks later, however, a letter was received from the king himself, informing Modyford as follows:

His Majesty cannot sufficiently express his dissatisfaction at the daily complaints of violence and depredation done by ships, said to belong to Jamaica, upon the King of Spain’s subjects, to the prejudice of that good intelligence and correspondence which His Majesty hath so often recommended to those who have governed Jamaica. You are therefore again strictly commanded not only to forbid the prosecution of such violences [sic] for the future, but to inflict condign punishment upon offenders, and to have entire restitution and satisfaction made to the sufferers.

After this letter came before the Jamaica Council, it ordered the seizure and restoration to their owners of a Spanish ship and a barque recently brought to Port Royal by Captain Robert Searle. Notice of this action was ordered to be sent to the governor of Havana. Also ordered was that:

“… all persons making further attempts of violence upon the Spaniards be looked upon as pirates and rebels, and that Captain Searle’s commission be taken from him and his rudder and sails taken ashore for security.” [Calendar of State Papers, America and West Indies, No. 789, Council of Jamaica Minutes.]

Evidence was soon provided that this order had to be taken seriously and could not—as too often had occurred in the past—be disregarded with impunity.

Near the end of the year, Captain Munro, who had obtained a Jamaican commission as a privateer, “turned pirate” and plundered several English ships on their way to Jamaica. Captain Ensor in the armed ketch Swallow pursued and overtook Munro’s vessel. Munro’s stubborn resistance resulted in the death of some of his crewmembers. The rest of the crew were taken prisoner, tried, convicted and hanged. They were left hanging in chains on the public gallows at the Point for all to see as they entered Port Royal harbour.

However, a certain ambiguity still persisted for one of Harry Morgan’s friends, Colonel William Beeston, recorded in his journal that, despite the proclamation, Captain Maurice Williams had brought in “a great prize with logwood, indigo, and silver.” And that several other privateers had left in search of prizes and, further, that Bernard Nicholas came in “with a great prize.”

Ambiguity could also be found when the Privy Council on the affairs of Jamaica recommended that the Lord High Admiral command all privateers in the West Indies to cease hostilities against the Spaniards and await further orders. However, these same orders gave the privateers permission to attack the Dutch at Curacao and their other plantations, after which they should be invited “to come and serve his Majesty in these parts.”

The foregoing illustrated that while England saw a use for the privateers-buccaneers in other conflicts—in this case in the Anglo-Dutch War—it now sought peace with Spain. Notwithstanding the official policy banning action against Spain for the sake of promoting trade, the prevailing view in Jamaica continued to be one of skepticism. In their view, there could never be peaceful trade with the Spanish provinces. One contemporary wrote:

The fortune of trade here none can guess, but all think that the Spaniards so abhor us that all the commands of Spain and the necessity of the Indies will hardly bring them to an English port….

A shared anxiety among the island’s leaders persisted. If the privateers could not dispose of their prizes at Port Royal as was their custom, would they transfer to Tortuga? If they did, the king would lose 1,000 to 1,500 men. Besides, if the buccaneers used Tortuga as a base to continue to attack the Spaniards, trade with Jamaica would be disrupted regardless of the king’s policy. Furthermore, without Port Royal to call their home, if England went to war with Holland, whose side would the buccaneers take? Would they turn against Jamaica and join with the Dutch at Curacao?

Many believed—and advised the governor of such—it would be advantageous to the Spaniards if the governor permitted the buccaneers to sell their prizes at Port Royal and become planters and hunters. This would keep them on the island and available to the king if needed in the future to take Tortuga or Curacao. And all agreed there were none more fit for such tasks.

Modyford seemed to see the wisdom of this advice, for he invited the privateers to return to Port Royal. Upon their arrival, he gave them permission to dispose of their captures and either become planters or accept letters-of-marque against the Dutch. In a letter to Lord Arlington,[1] England’s secretary of state, Modyford, stated Bertrand d’Ogeron, the French governor of Tortuga, had given commissions to some English privateers. He would deal with Tortuga after he had finished with the Dutch, he wrote.

[1]Henry Bennet, 1st Earl of Arlington KG, PC (1618–1685), who was Baron Arlington at the time (1668). In 1672, he was made Earl of Arlington and Viscount Thetford, and was re-granted the title of Baron Arlington, with a special remainder allowing it to descend to male and female heirs, rather than male heirs only, as was customary with most peerages. Lord Arlington was a member of the pro-Spanish faction at court.

Nevertheless, Modyford seemed confident that those privateers would return to Jamaica and take commissions against Holland. Some six weeks later, he was able to announce with considerable satisfaction that “upon my gentleness towards them, the privateers come in a-pace and cheerfully offer life and fortune to his Majesty’s service.”

And the king’s policy did seem to be having the desired effect. Reports claimed many of the former soldiers had become hunters and killed an estimated thousand hundredweight of wild hogs per month, for which they found an eager market at a good price. While several others focused on developing their land-grants into productive income-generating estates and plantations.

❦❦❦

Relationships between England the Holland deteriorated over far-away conflicts in the East Indies. England demanded reparation be paid by the Dutch for damages they had done to ships and factories of the East India Company. England displayed its resolve by appropriating an unprecedented £2,500,000 to equip the Royal Navy. The two nations had been engaged in open hostilities in both the East and West Indies, the Mediterranean, at many places on the west coast of Africa, and in North America. Supremacy in international trade was at stake. War was not actually declared by England until 17 Mar 1665, however.

Before embarking, Sir Edward made his will, bequeathing his plantation to his two sons. To his second daughter, Mary Elizabeth Morgan, he left his house in London, mortgaged for £200, and his “pretence upon Lanrumney,” representing his claim on an estate in Wales. The remainder of his property was to be divided between his other three daughters and his youngest son. The rights in his pension of £300 annually and in his father’s will, he passed to his daughter Mary Elizabeth.

They are chiefly reformed privateers, scarce a planter amongst them, being resolute fellows, and well armed with fusees and pistols. Their design is to fall upon the Dutch fleet trading at St. Christopher’s, capture St. Eustatia, Saba, and Curacao, and on their homeward voyage visit the French and English bucca-neers at Hispaniola and Tortugas. All this is prepared by the honest privateer, at the old rate of no purchase no pay, and it will cost the King nothing considerable, some powder, and mortar pieces. [Calendar of State Papers, America and West Indies, No. 979, Modyford to Arlington, 20th April, 1665.]

The Jamaicans met with little opposition. As they hit the beach, Sir Edward leapt from his craft and led the charge at the outnumbered Dutch islanders. Unfortunately, the old warrior died abruptly from heart failure—likely due to over-exertion. Colonel Cary took command, and, about three weeks later, Major Richard Steevens took the tiny Dutch island of Saba.

Colonel Cary in his official narrative of the expedition reported that: “The Lieutenant-General [Morgan] died, not with any wound, but being ancient and corpulent, by hard marching and extraordinary heat fell and died, and I took command of the party by the desire of all.” [Source: Calendar of State Papers, America and West Indies, No. 1086, Narrative by Colonel Theod. Cary of the expedition against the Dutch.]

The expedition captured four colours, twenty cannons, many small arms and munitions, 942 slaves and several horses, goats and sheep. Besides, more than three hundred Dutch inhabitants were deported. However, any chance of further success was soon lost, for the privateers dispersed in search of other spoils. Consequently, Colonel Cary and his officers were forced to return to Jamaica, leaving their spoils behind. A Dutch squadron recovered most of the abandoned spoils before the end of the same year. Furthermore, the expedition never did make an attempt on Curacao, nor did it even try to expel the French from Tortuga.

At least in Modyford’s eyes, Sir Edward Morgan’s reputation was not diminished, notwithstanding his venture’s complete failure. In fact, after knowing the man for only a short time, the governor had formed a high opinion of him, as indicated by this remark, “I find the character of Colonel Morgan short of his worth and am infinitely obliged to his Majesty for sending so worthy a person to assist me, whom I really cherish as my brother ….”

Comments

Post a Comment

Your feedback is appreciated: