Chapter 15.1 – Maracaibo, part II

By this time, the privateers had plenty of fresh beef and pork for their homeward voyage, but lacked what Morgan referred to as “dry provisions.” Gibraltar, located on the south-east shore of Lake Maracaibo nearly 100 miles from the sea, was a small town that was rich in cocoa walks and grain crops that were just the sort of provisions Morgan needed.

A plantation of cocoa trees (Theobroma Cacao) usually planted in rows with taller trees planted in between to shade them. The shadow of the taller-growing trees protects the young cocoa tree against the burning sun or strong wind. After five years, it is strong enough to survive and start producing cocoa.

The admiral sent a few of the prisoners on ahead to Gibraltar hoping they could convince their countrymen to surrender. But to no avail.

After the main body of privateers arrived the next day, Morgan, while making a show of preparing for a frontal attack on the garrison, sent his French guide with a party of privateers through the woods to cut off retreat. The garrison had second thoughts about defending the town and, after spiking their guns, took to the nearby hill, carrying their worldly possessions. The privateers were in hot pursuit and captured several inhabitants and a considerable number of slaves. One of the slaves offered to guide Morgan to “a certain River belonging to the Lake, where he should find a Ship and four Boats richly laden with goods that belonged to the Inhabitants of Maracaibo.”

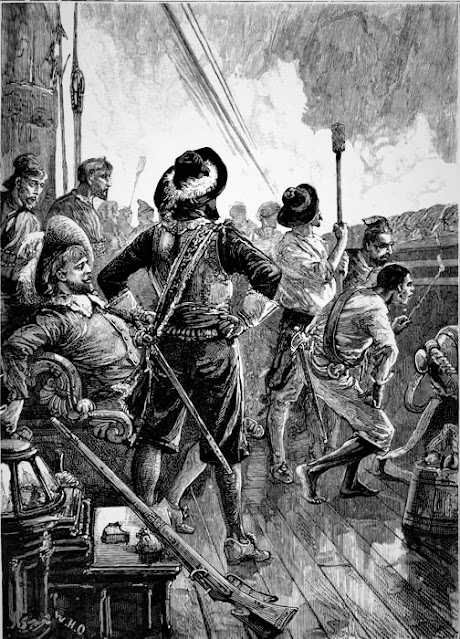

|

| MORGAN’S ATTACK ON GIBRALTAR The Sea Its Stirring Story of Adventure, etc. by Frederick Whymper |

Morgan split his forces. He sent 200 men in large boats towards the river the slave had mentioned. He took a second force of 250 men with him to look for the governor. The governor had retreated to a fort on a small mid-river island. However, before Morgan reached the island, the man had moved to a mountain stronghold reachable only by a very steep and narrow path. Morgan planned to give pursuit, but the rains came—buckets of it. Everything got soaked, including their prisoners, many of whom fell ill and died.

Seeing the futility of the further pursuit of the governor, Morgan returned to Gibraltar after 12 days. Two days later, the other group arrived at the town, bringing four boats and more prisoners. Most of the goods they had hoped to find had been taken away and hidden by the prewarned Spaniards. However, the Spaniards left in such haste they abandoned both the ship and the four boats partially loaded with a considerable amount of booty. These the privateers brought back with them to Gibraltar.

Much has been made in some accounts of the cruel treatment of the Spanish prisoners, many of whom were said to have been tortured. At least one historian, however, disputes that Harry Morgan ordered this or was even aware of it. Charles Leslie wrote the following:

The Truth of the Matter stood thus: Morgan having prevailed on a Slave to discover where the Governor of Gibraltar and the most considerable of the Inhabitants with their Effects lay concealed, went immediately with Two Hundred Men to attack them there. He likewise ordered Two Hundred and Fifty Men to march to a River which discharges itself into the Lake, in search of a Ship and four Boats, which were richly laden with Goods, and in the time of their Absence all the above named Cruelties were committed.

In thirteen letters, Charles Leslie, whose family had strong Caribbean interests, covers Jamaica’s early history, including the exploits of Sir Henry Morgan. Leslie’s book first appeared as “A new and exact account of Jamaica” in Edinburgh in 1739, followed by a re-titled second edition, London, 1740, which contained an additional chapter. A Dublin edition followed in 1741, and a French translation in 1751.

Leslie also noted that he had “seen a Manuscript writ by one who was concerned on the Expedition, which contains a Journal of their whole Procedure. This Relation, now in the hands of a considerable Planter here, vindicates Morgan from these black Aspersions.”

After about a month, the prominent Spaniards who the privateers held as prisoners agreed to a ransom amount for their lives and to save the town. The admiral steadfastly refused to give up the slave who had acted as his informer and guide, for he believed that the Spaniards wanted the man so that they could “punish him according to his deserts.” [Esquemeling] Morgan never received the full amount of the ransom, but instead received four prominent citizens as hostages to act as surety for the remainder.

With his fleet fully provisioned, Morgan set sail for Maracaibo. The privateers had captured five vessels on Lake Maracaibo that they believed could make the voyage home. Most were small, but one was a large merchant ship from Cuba, which was bigger than any of the privateer fleet’s original eight vessels. The voyage across Lake Maracaibo took four days, and when his fleet arrived at the town Morgan found the place deserted but for “a poor distressed old man, who was sick.” From him, Morgan learned that three Spanish warships had taken up positions at the strait leading from Tablazo Bay to the open sea and were waiting there to block his escape. He also learned that Fuerte de La Barra on San Carlos Island, which commanded the channel to the sea, had been repaired and re-garrisoned by the Spaniards.

Morgan dispatched a ship to reconnoitre. Her captain returned with news that the largest of the three Spanish men-of-war carried 40 guns and her consorts 30 and 20, respectively. Furthermore, all three appeared to be well manned. If Lake Maracaibo could be thought of as a bottle, then the Spaniards had truly put a cork in it. Morgan’s fleet was trapped with little prospect of escape.

THE SPANISH SQUADRON OPPOSING Morgan’s fleet was what remained of the formidable Armada de Barlovento, a fleet created by Spain to protect its American territories from attacks by its European enemies, as well as attacks from pirates and privateers. The fleet of three men-of-war was commanded by Vice-Admiral Don Alonso del Campos y Espinosa.

The Armada de Barlovento had, until recently, consisted of five warships under the command of Captain-General Don Agustin de Diostegui, but its two most powerful men-of-war had been recalled to Spain along with Diostegui, leaving Don Alonso in command of a 412-ton galleon or frigate, Magdalena, armed with 36 canons and 12 swivel guns, a 218-ton frigate, San Luis, with the combined total of 36 cannon and swivel guns, and the 120-ton Nuestra Señora de la Soledad, with 16 canons and eight swivel guns. And, although these three ships were classified as only small to medium-sized men-of-war, each one would be more than a match for any ship in Admiral Morgan’s fleet.

Biographers Peter Earle and David Marley both list la Soledad at 50 tons. Earle says it had 10 guns, while Marley claims it had 14. Other accounts, however, list the ship as being larger and more heavily armed than this.

When the fleet first arrived in the Caribbean, it was stationed first at San Juan, the capital of Puerto Rico, but soon moved to Havana, Cuba. At about the time Diostegui returned to Spain, Don Alonso received news that the Jamaican privateers were gathering at Île-à-Vache intending to join the French flibustiers in an attempt on Cartagena. He immediately sailed east along the northern coasts of Cuba, Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, hoping to sail far enough eastward to gain a wind advantage on Morgan’s fleet. (Along the Spanish Main, trade winds (prevailing winds) blow from east to west.)

When the names of Puerto Rico and its capital were being officially registered, the names were reversed in error. The island should have been named San Juan and its capital Puerto Rico (Rich Port).

At the Mona Passage, between Hispaniola and Puerto Rico, however, Don Alonso heard from a Dutch merchantman that Santo Domingo was in danger of an imminent attack from several French ships. Therefore, deciding to detour and reinforce Santo Domingo’s garrison, he altered course and arrived at Hispaniola’s capital on 25 Mar 1669. A French attack never materialized, but Don Alonso’s visit was not a waste of time. He learned that a Jamaican privateer fleet had been seen as it sailed by Santo Domingo. Later, he learned from another source that Morgan’s fleet was in Lake Maracaibo.

The Armada de Barlovento arrived off the Bar of Maracaibo in the Gulf of Venezuela in mid-April, and once Don Alonso had determined Morgan’s flotilla was still within the lake, he set his trap.

Don Alonso gave orders to re-garrison and rearm Fuerte de La Barra by digging up some of the cannons Morgan’s men had spiked and re-drilling their touchholes. He also added spare cannon from a man-of-war the Spaniards had salvaged weeks earlier and two 18-pounder guns from Magdalena. Don Alonso then sent messages inland for reinforcements in the form of ships and men he would need should a naval and land assault against the privateers become necessary. Next, he lightened his men-of-war to lessen their draught and, floating them across the bar, positioned them just inside Tablazo Bay.

Don Alonso’s flagship, Magdalena, took up a position west of the island of Zapara, while Soledad and San Luis anchored at equal distances to starboard. Thus, the channel that ran between San Carlos and Zapara islands was blocked and the lake beyond blockaded. From that superior position, Admiral Don Alonso del Campos lay in wait to engage Admiral Harry Morgan’s fleet in what would be known as the Battle of the Bar of Maracaibo.

Comments

Post a Comment

Your feedback is appreciated: