Chapter 15.2 – Maracaibo, part III

|

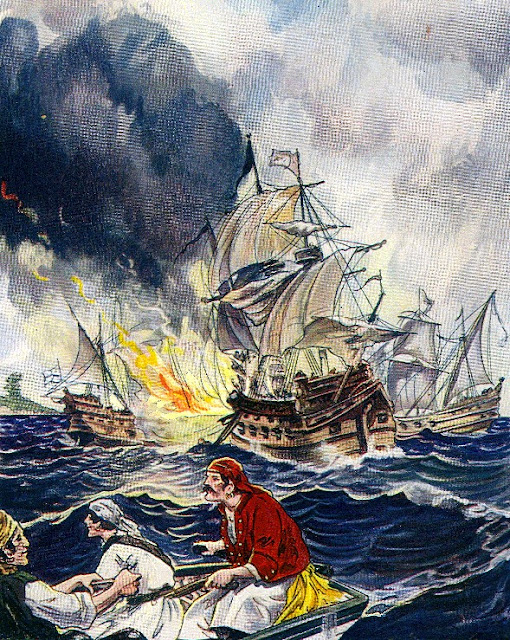

| Fireship at Maracaibo (cropped) | by Geo. Alfred Williams |

The prospect of trying to force a way past the Spanish blockade could not have been a pleasant one for Admiral Morgan. He expected word of his activity in Lake Maracaibo to reach other Spanish settlements in the region. Then it would be only a matter of time before he would have to face an even larger Spanish force. Morgan remained undaunted, however, and wrote a message to the commander of the Spanish squadron. He demanded safe passage to the sea along with payment of a ransom for the town of Maracaibo. He threatened if the ransom was not paid, to set the town aflame.

Don Alonso responded two days later. He explained his position and offered free passage to the privateers so long as they returned all their booty. The following are excerpts from a translation of the Spanish commander’s 24 Apr 1669 letter. (There are two versions of this letter, but I believe this version is the one reproduced in Morgan’s own report.)

My intent is to dispute with you your passage out of the lake and follow and pursue you everywhere, to the end that you may see the performance of my duty. Notwithstanding, if you be contented to surrender with humanity all that you have taken, together with the slaves and all other prisoners, I will let you pass freely without trouble or molestation; upon condition that you retire home presently to your own country.

Don Alonso closed his letter with a threat:

But in case that you make any resistance or opposition unto those things that I proffer unto you, I do assure that I will command boats to come from Caracas, wherein I will put troops, and coming to Maracaibo, will cause you utterly to perish, putting you every man to the sword. This is my last and absolute resolution. Be prudent therefore, and do not abuse my bounty with ingratitude. I have with me very good soldiers, who desire nothing more ardently than to revenge upon you and your people all the cruelties and base infamous actions you have committed upon the Spanish nation in America.

Soon after receiving this letter, Harry Morgan assembled his officers and men in Maracaibo’s market-square and read the letter aloud in English and then in French. Afterwards, he called for a vote on whether they should surrender their plunder in exchange for a safe passage across the bar rather than make a fight of it. To a man, they shouted that they would rather die than give up anything they had taken with such hard effort. It is unlikely a single man in that market-square believed the Spanish admiral would keep his word and let them sail out of the lake unmolested. Such was not their experience with the Spanish dons of the 17th Century. They knew only too well that many an Englishman had been put to death or clapped in irons after accepting similar terms of surrender from a Spaniard like Alonso del Campo.

With his privateers’ will made clear, Morgan attempted to negotiate a safe passage a second time. This time, he sent two of his officers to propose to the Spanish admiral that his privateers leave Maracaibo without doing any further damage or receiving a ransom for the town. Further, he offered to surrender half of the slaves he had taken, to liberate of all his prisoners, and to free the four prominent hostages he had brought from Gibraltar, all without further payment.

These terms were firmly rejected by Don Alonso del Campo, however. He declared Morgan’s terms to be dishonourable, and he replied that unless the conditions he had already offered were accepted within two days, he would begin an attack. By this time, though, Morgan had developed a plan to force a passage through the strait.

Some accounts credit an anonymous source from among the privateers for this plan, but the admiral claimed full credit for himself. Morgan set his men to work, preparing his fleet for battle. Work on two of his ships, though, was of special importance. One, a sloop, the privateers pretended to convert into a fire-ship, something the Spaniards would expect to hear about from their spies. The other was the large Cuban ship captured at Gibraltar, which the privateers prepared as Morgan’s new flagship. They added more cannons and made a show of manning her with many men heavily armed with swords, muskets, and bandoliers. Or so it would seem to any distant observer.

In fact, the sloop as a fire-ship was a ruse to misdirect the Spaniards and disguise the real fire-ship, which was the large Cuban ship. They spread all the pitch, tar and brimstone they found in the town throughout the larger craft. Then they lay about large quantities of powder and palm leaves smeared with tar. The cannon that could be seen pointing out through freshly cut portholes were imitations made of hollowed out and painted logs. Besides, the armed men on the deck were really “scarecrows”—arrangements of wood pieces dressed up with hats and adorned with weapons to imitate armed crewmen. By the time they were finished, the Cuban ship was fully disguised. To the Spaniards looking on, Admiral Morgan’s flagship, his flag streaming in the wind, had decks that bristled with cannons and bore heavily armed boarding parties.

Brimstone is sulphur in the form of a lemon-yellow coloured stone. When a brimstone is exposed to air and a match is put to it, it burns like a liquid fire and emits noxious fumes. The stone melts like wax, but the dripping is a peculiar thick fire that acts like burning wax.

The male prisoners had been placed aboard one ship, and the women and the most valuable plunder in another. In a third, they placed the less valuable cargo. All three were crewed by only twelve sailors leaving as many privateers as possible for the other vessels and available for hand-to-hand combat. As well, twelve reliable men were selected to sail the fire-ship.

After a week of preparation, Admiral Morgan’s 13 ships sailed on the afternoon of 30 April to face the three Spanish ships that were still anchored in the middle of the channel. With the sun setting, Morgan gave orders to anchor just out of the Spanish guns’ range, daring the Spaniards to come at him.

At daybreak the next day, Morgan saw the Spaniards had not moved. So, taking the initiative, he gave his ships the signal to weigh anchor and sail towards the Spanish men-of-war. Sailing with the tide and favourable winds, the fire-ship led the privateer flotilla. They quickly closed with the enemy, who now also cleared for action. The fire-ship was deftly handled and bore down on the towering Magdalena as if Morgan intended to board her. And before the Spanish flagship discovered what was about to happen, the Cuban ship's skeleton crew flung grappling irons across to the Magdalena, locking both vessels together in a mortal embrace. Immediately after this, the privateer crew lit fast-burning fuses and abandoned the disguised fire-ship.

The Spaniards were shocked and perplexed by Morgan’s plow. They were confident they would prevail in any encounter with the privateers. Their confusion worsened when they saw flames racing about on what they had assumed was Morgan’s flagship. Recognizing something was dreadfully wrong, Magdalena’s crew struggled to fend off the smaller privateer with boathooks and pikes. But to no avail.

The fire reached the Spanish flagship, forcing crewmembers to clamour over the side and leap into the uncertain waters below. Streaks of fire ran through the rigging and leaped onto the sails of both ships like angry spirits consuming everything in their paths. Within minutes, violent explosions on board the deserted fire-ship spread showers of embers and blazing fragments of wood. Finally, as if it had been struck by a bolt of lightning, Magdalena’s magazine blew up. Her hull broke apart completely and sank, leaving many of her crew swimming desperately for their lives or clinging grimly to floating spars.

Without the loss of one privateer, the pride of the Armada de Barlovento was lost.

|

| Fortress on San Carlos Island |

Don Alonso and many of his surviving soldiers and seamen eventually crowded into Fuerte de La Barra on San Carlos Island, which they further reinforced with whatever they could salvage from the San Luis wreck. This fort was now a more formidable barrier to the open sea than when Morgan’s privateers easily captured it. But the privateers were flushed with victory and felt nothing was impossible. For the rest of that day, Morgan’s men assaulted the fort, and when they were driven back, they took cover and fired their muskets at anything that showed above the high walls of the fort.

Meanwhile, Morgan moved his flag from Lilly to the captured Soledad. Then he returned to Maracaibo to refit and prepare to do battle once more. In his temporary headquarters at Maracaibo, Morgan assembled his prisoners for questioning. Among them was the former pilot of Soledad, who was not a Spaniard and who turned informer. He told about the Armada de Barlovento’s arrival in the West Indies and the events leading up to the blockade of Lake Maracaibo. He also told how Don Alonso had ignored a warning about the fire-ship rouse because the Spanish don thought the privateers had not “wit enough to build a fire-ship.” For his cooperation, the pilot received his freedom and chose to join the privateers. He then told Morgan that Magdalena had a cargo of silver worth about 40,000 pieces of eight.

Morgan ordered repeated attacks on the fort, without success and with the loss of 30 lives. By then, many of the inhabitants just wanted to be rid of the privateers and agreed to pay for peace. They gave the privateers 20,000 pieces of eight and 500 cattle in return for the hostages and Morgan to leave Maracaibo intact. The privateers received the cattle and some of the coin up front. Later, while the buccaneers preserved the beef for their voyage, they got the remainder of the coin. However, Morgan did not release the prisoners, for he knew full well that Don Alonso had not been party to the agreement and was unlikely to allow his flotilla to pass the fort.

While the main force of privateers was attacking the fort and Morgan was negotiating the ransom, the admiral had also directed others to dive on the sunken Magdalena. They recovered silver worth more than 20,000 pieces of eight. Included were quantities of coin that had been melted together by the heat of Magdalena’s fire to form lumps of silver bullion.

Admiral Morgan knew his time on the lake was running out, for surely the Spaniards in the region knew of his presence, and reinforcements would arrive shortly. He made another attempt to negotiate. This time he promised the prisoners that if they could persuade Don Alonso to let them pass, they would be freed without paying a ransom. However, if the Spanish commander disagreed, every prisoner would be hanged. Again Don Alonso refused to strike a bargain, though, not all the Spaniards shared his view.

Morgan did not hang his prisoners, but chose to try another ruse.

To prepare for escape through the heavily guarded straight, Morgan gave orders to share out the plunder so it would not be concentrated in one or two ships and possibly all be lost in the upcoming battle. Edward Long, the much-quoted historian, places the booty’s value at 250,000 pieces of eight. [The History of Jamaica, 1774]. This was about the same as the privateers took from Portobello. Long is clear that his estimates do not include “quantities of silks, linens, gold and silver lace, plate, jewels, and other valuable commodities.” Esquemeling wrote that the booty amounted to 250,000 crowns in money and jewels, besides a great quantity of merchandise and slaves. Sir Thomas Modyford, on the other hand, wrote that the buccaneers received only £30 per man, half their Portobello share. The differences can probably be accounted for by the buccaneer tradition of pre-sharing some of their spoils before returning to Jamaica, where there would be an official division done by the Admiralty Court.

As part of the escape plan, Admiral Morgan moved his flotilla closer to shore and well out of range of the fort’s guns. Next, he oversaw the loading of several open boats with heavily armed privateers and watched as they rowed ashore. They worked only during the day, taking care that the Spaniards in the fort saw everything they did. However, each boat landed at a point on the shore where thickets obscured the Spaniards’ view. After waiting for about the time Don Alonso would expect them to have unloaded the boats, two buccaneers rowed the empty boats back to the ships, on the side farthest from curious eyes at the fortress.

Of course, the privateers never really landed. Instead, they lay down in the bottom of their boats once out of sight and made the return trip to the ships. By repeating this several times, Morgan hoped that Don Alonso would believe a large force planned a night assault by land on the fortification’s most weakly defended side. Taken in by this simple ruse, the don ordered several of his great guns moved, so they pointed landward. This decreased the number of cannons covering the channel and improved the likelihood of the privateers escaping Lake Maracaibo.

Shortly after nightfall, Morgan’s ships silently slipped their anchors and “by the light of the moon, without setting sail” drifted gently with the ebbing tide until they came abreast of the fort. At that point, the privateers spread sail and made a dash for the open sea.

When the Spanish sentries alerted Don Alonso, he realized there would be no land-based assault. But it was too late, for Morgan’s escaping flotilla benefitted from a favourable wind and was slipping quickly past the fortress. A barrage from Fuerte de La Barra’s battery did little damage, for too many of its cannons were pointing inland. They could not be brought to bear in time to be much of a factor. According to Esquemeling, the privateers “lost not many of their men nor received any considerable damage to their Ships.”

The following morning, when out of reach of Fuerte de La Barra’s guns, Admiral Morgan released the remainder of his prisoners and the Gibraltar hostages. Then, just before he departed, he “ordered seven great Guns with Bullets to be fired against the Castle, as it were to take leave of them. But they answered not so much as with a musket shot.” [Esquemeling] Afterwards, Morgan’s fleet set a course across the Caribbean Sea towards Port Royal, and so ended the Battle of the Bar of Maracaibo.

❦❦❦

I BELIEVE IT IS worth repeating here that even after threatening to kill the Spanish prisoners for nonpayment of ransom, Harry Morgan, set them free and unharmed, unlike the treatment Englishmen and other Jamaicans received regularly at the hands of the Spaniards. But that was Harry Morgan’s way. Time and again, he freed prisoners even when their countrymen had reneged on paying some or all of their ransom.

Despite the cruelties with which Morgan is charged by many, his own account stated that, during his occupation of Portobello, he offered “several ladies of great quality” and other prisoners their release so they could seek refuge in the President of Panama’s camp outside the city. But the ladies refused, saying “they were now prisoners to a person of quality, who was more tender of their honours than they doubted to find in the President’s camp among his rude Panama soldiers.”

It is also notable that official Spanish accounts of Harry Morgan’s raids on Cuba and the Spanish Main do not seem not to have the number of libellous accusations of wanton cruelty, attributed to Morgan personally, as do accounts contained in Esquemeling’s popular book, History of the Bucaniers. I find it curious that readers find truth in the words of an admitted buccaneer and pirate, John Esquemeling, who held a personal grudge against Morgan, but refuse to accept the word of Henry Morgan himself, a prominent landowner, council member, custos, general, admiral, governor and English knight.

Comments

Post a Comment

Your feedback is appreciated: